Linguistics

>The dispersal of the Indo-European language family from the third millennium BCE is thought to have dramatically altered Europe’s linguistic landscape. Many of the preexisting languages are assumed to have been lost, as Indo-European languages, including Greek, Latin, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic and Armenian, dominate in much of Western Eurasia from historical times. To elucidate the linguistic encounters resulting from the Indo-Europeanization process, this volume evaluates the lexical evidence for prehistoric language contact in multiple Indo-European subgroups, at the same time taking a critical stance to approaches that have been applied to this problem in the past. *Part I: Introduction* Guus Kroonen: A methodological introduction to sub-Indo-European Europe *Part II: Northeastern and Eastern Europe* Anthony Jakob: Three pre-Balto-Slavic bird names, or: A more austere take on Oštir Ranko Matasović: Proto-Slavic forest tree names: Substratum or Proto-Indo-European origin? *Part III: Western and Central Europe* Paulus S. van Sluis: Substrate alternations in Celtic Anders Richardt Jørgensen: A bird name suffix *-anno- in Celtic and Gallo-Romance David Stifter: Prehistoric layers of loanwords in Old Irish *Part IV: The Mediterranean* Andrew Wigman: A European substrate velar “suffix” Cid Swanenvleugel: Prefixes in the Sardinian substrate Lotte Meester: Substrate stratification: An argument against the unity of Pre-Greek Guus Kroonen: For the nth time: The Pre-Greek νϑ-suffix revisited *Part V: Anatolia & the Caucasus* Rasmus Thorsø: Alternation of diphthong and monophthong in Armenian words of substrate origin Zsolt Simon: Indo-European substrates: The problem of the Anatolian evidence Peter Schrijver: East Caucasian perspectives on the origin of the word ‘camel’ and some notes on European substrate lexemes

I have a question for folks here, mainly around English linguistics but would love to hear of parallels in other languages. If you're not big on cats, just skip the next paragraph, which I've include for the context to be clear and show why I have provided the picture. This morning, one of my cats was acting up a bit, hopping on the table where I have an electronics project, and searching for something to pilfer. In order to halt this behavior, I distracted him with a good deal of play with *his* toys (he is very athletic, so, lots of tossing a toy mouse for him to chase, then walking over to where he's left it because he doesn't fetch anymore). The image is of the culprit now that he's worn out. While trying to achieve this state, I had a modified aphorism occur to me: > Idle cats are the Devil's playground. It occurred to me then that I'm not sure if there is an extant term to describe taking an existing aphorism and modifying it while still conveying the same or similar meaning. For those not familiar, the original aphorism is "Idle hands are the Devil's playground" (apparently of biblical origin), meaning roughly that busy people don't often get into trouble or conversely that bored people will get into mischief. There is a term, if informal, to describe, often intentional, mismatch of parts of aphorisms (ex. "Not the sharpest egg in the attic"), malaphor. Can anyone think of a similar extant term for a modified aphorism? If not, after trying multiple prefixes, I think that the least clunky seems to be "transaphor" (trans- meaning to change). Anyone have thoughts on the matter?

www.theguardian.com

www.theguardian.com

cross-posted from: https://feddit.uk/post/14265279 > > The upward intonation, the guttural “ck” and even the cheeky comeback to win the argument: at just 19 months old, baby Orla has mastered the crucial elements of speaking like a scouser. > > > >Impressively, the toddler who featured in a viral video this week appears to have done so without the need for actual words. > > > >A clip posted on TikTok, and now viewed more than 20m times, shows Orla babbling in a Liverpudlian accent as her babysitter, Olayka, tries and fails to coax her into taking a nap. Scientists say that the cute exchange is also a vivid illustration of the processes by which babies acquire language – and the surprising role of accents. > > > > Babies are so tuned in to the musical ups and downs of speech that even as newborns they cry in distinctive ways that reflect the languages that they have heard while in the womb. > > > >In one 2009 study, Prof Kathleen Wermke, a pioneer in the field of speech development at the Würzburg University in Germany, found that French infants tend to wail on a rising note and German babies favour a falling melody and other patterns have been seen for Mandarin, Swedish and African languages. “When I started 40 years ago, if I told people I was recording babies crying and making high-pitched sounds they’d look at you and think ‘Is this really science?’,” she said.

www.livescience.com

www.livescience.com

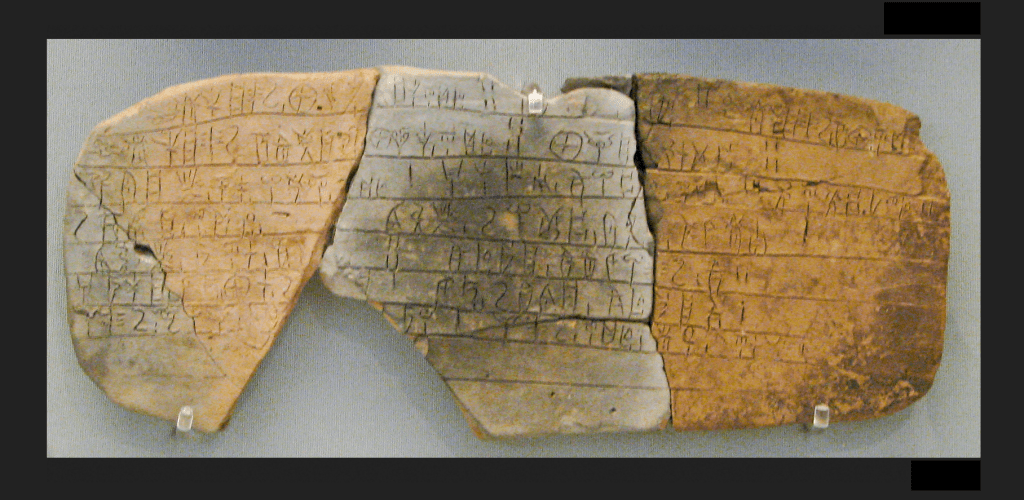

I'm sharing this here mostly due to the alphabet. The relevant region (Tartessos) would be roughly what's today the western parts of Andalucia, plus the Algarve. [Here are the news in Spanish](https://www.csic.es/es/actualidad-del-csic/el-csic-investiga-un-abecedario-hallado-en-la-tablilla-de-pizarra-del-yacimiento-de-casas-del-turunuelo), for anyone interested. The number of letters is specially relevant for me - 32 letters. The writing system is [a redundant alphabet](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southwest_Paleohispanic_script), where you use different graphemes for the stops, depending on the next vowel; and it was likely made for a language with five vowels, so you had five letters for /p/, five for /t/, five for /k/. Counting the "bare" vowels this yields 20 letters; /m n s r l/ fit well with that phonology, but what about the other seven?

cross-posted from: https://programming.dev/post/15125500 > xkcd \#2942: Fluid Speech > > https://xkcd.com/2942 > > [explainxkcd.com for \#2942](https://explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/2942:_Fluid_Speech) > > Alt text: > > Thank you to linguist Gretchen McCulloch for teaching me about phonetic assimilation, and for teaching me that if you stand around in public reading texts from a linguist and murmuring example phrases to yourself, people will eventually ask if you're okay.

www.bbc.com

www.bbc.com

> they were taking part in an unusual experiment, which involved tracking their own voices over time. This was done by making 10-minute recordings every few weeks. They would sit in front of a microphone and repeat the same 29 words as they appeared on a computer screen. *Food. Coffee. Hid. Airflow.* > One of those changes was the "ou" sound in words such as "flow" and "sew" that shifted towards the front of the vocal tract. I'm not actually sure what sound change they're describing there. Can anyone explain with examples or IPA? edit: Cheers for the answers (turns out I misunderstood which part is the vocal tract)

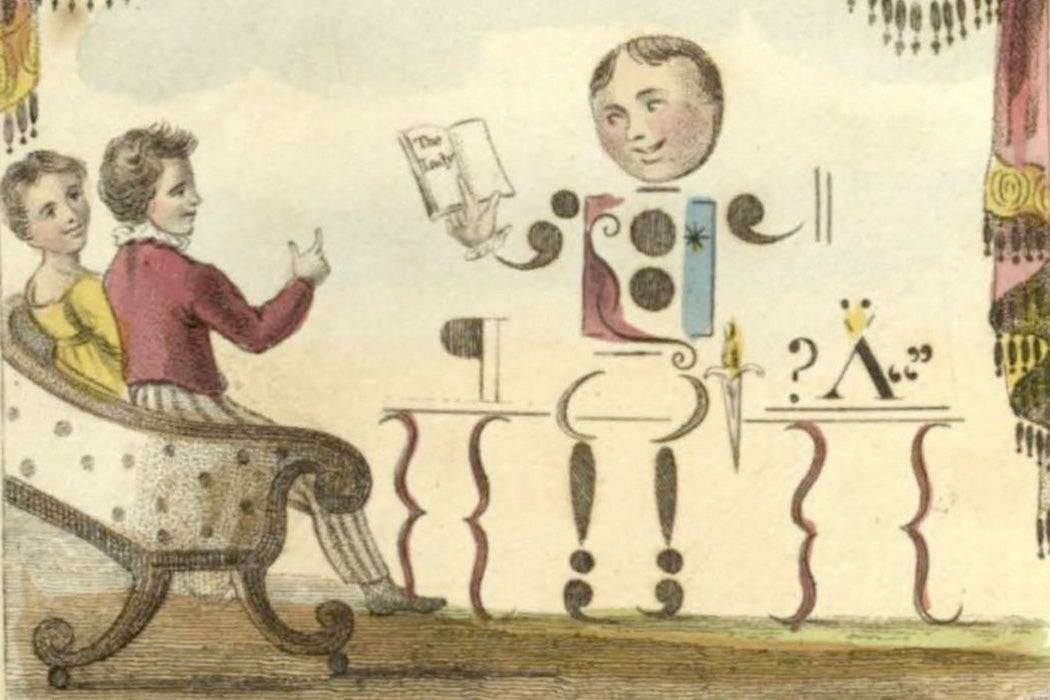

daily.jstor.org

daily.jstor.org

Hi, I'm a casual linguistics nerd (no degrees), speaking Philippine English with heavy American influence. My accent of English has pre-nasal /æ/ raising and I've caught myself raising it in other places like before /g/. When I look at English language learning videos (out of curiosity) I have not found anyone mention /æ/ raising in them. Why is this case?

I'm sharing this mostly as a historical curiosity; Schleicher was genial, but the book is a century and half old, science marches on, so it isn't exactly good source material. Still an enjoyable read if you like Historical Linguistics, as it was one of the first successful attempts to reconstruct a language based on indirect output from its child languages.

www.sci.news

www.sci.news

[Link for the Science research article](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aav3218). The observation that societies without access to softer food kind of avoided labiodentals is old, from 1985, but the research is recent-ish (2019).